In 2019, the International Dragon Boat Federation (IDBF) made the bold move to include a new division for future world championships; Paradragons. Composed of paddlers with varying abilities ranging from overcoming psychological trauma to navigating physical challenges, this is a landmark achievement for the international disability community.

Beyond reinforcing the inherent inclusiveness of dragon boating, the new division “is a critical step in recognizing the true power of disabled athletes for the fierce competitors they are.”

On August 7-13, 2023, Canada will be launching its very first National Para team at the 16th World Dragon Boat Racing Championships to be held in Pattaya, Thailand. With a strong and diverse team, the group is actively contesting assumptions about ability and showing that the impossible is possible.

We spoke to members of Canada's inaugural National Para Dragon Boat team, and here’s what they had to say:

What is a Paradragon?

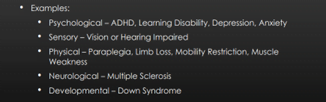

While the common perception of disability is of a physical nature, the IDBF defines paradragons as “paddlers who have some form of physical, psychological, neurological, sensory developmental or intellectual impairment.”

Coaches are advised to refrain from making assumptions about ability, to collectively find solutions, and to not treat para athletes any differently from their counterparts.

But You Don’t Look Disabled

According to Coach Katy Milne, most of the para athletes on the boat are dealing with ‘invisible disabilities’ or emotional or psychological challenges such as pervasive anxiety, depression or post-trauma (often only known to the coach and captain). As the challenges are not apparent (ex: not missing a limb or hearing/visual aid), these para athletes are challenging common conceptions.

For those dealing with psychological issues, it takes courage to share one’s story as there is often stigma and judgment. Through hesitating to disclose details however, individuals often do not receive needed accommodations or considerations.

By accepting individuals as they are, everyone gains in sensitivity and awareness, not to mention committed paddlers who just need the chance to prove themselves.

You’re One of Us – Period.

The Canadian National Para team is aiming to have a small PD1 (small boat with all para athletes), a small PD2 (where para athletes make up half of its boat; not including the drummer and steerperson) and a standard PD2.

While Simon Lamy from Trois Rivières, Québec is not a paradragon himself, he has particular insight due to having a sibling with cerebral palsy. “Being with my brother [has] made me a deeply different person for life,” he observed.

An engineer as well as a dragon boat captain for years, Lamy has a compassionate yet logical side.

For instance, at the training camp in Montreal, he offered to tape his paddle yellow for the visually-impaired paddler behind him (normally a pacer, she had not needed to follow before), knowing how critical it is for the boat to be in sync. Coach Milne was so impressed with this subtle yet impactful gesture for a fellow paddler, she remarked, “[You] can’t teach that type of inherent empathy.”

Photo credit: Simon Lamy

One of the Gang

Bronwyn Funiciello is one of three visually-impaired paddlers on the boat.

Funiciello’s journey started 18 years ago on the Dragon Eyes team sponsored by Ottawa’s National Capital Visually-Impaired Sports Association in Ontario. When an injury put their steerer out of commission in 2005, she subbed with former rivals, the Ottawa Police Blue Dragons team. They had often engaged in friendly races, with the police crew (composed of officers and civilians) frequently being bested by the ‘blind team’. “I was hooked,” noted Funiciello, quipping, “I pretty much never looked back.”

She loved the constant pursuit of self-improvement and the fact that “I have never been made to feel any different from any other paddler. I am expected to paddle just as hard. No excuses or exceptions.”

In response to the (well-intentioned) tendency of others to be overprotective and to speculate on abilities, Funiciello reinforced, “it's not [like] there are 19 paddlers and ‘the blind one’- we are 20 paddlers.”

Photo credit: Bronwyn Funiciello

Accepted For Who and How You Are

When someone has gone through a traumatic experience, they emerge irreversibly damaged and indelibly changed. It can be difficult to manage the day to day, let alone be vulnerable and share their story with others.

Such is the case for Karen Bahrey, a mental health professional from Victoria, British Columbia. One of the most accomplished paddlers on board (she has paddled at 3 club crew worlds), she was attacked by a client during a session in May 2017, sustaining multiple head injuries and Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). “Every time that I had to go [outside], there was too much stimulus for my brain to cope with…and I would have to retreat to my room again.”

Dragon boating has been integral for her to regain control in her life. Bahrey knows she can count on her coach and team to shield her and give her time to recoup if and when needed, no questions asked.

Photo credit: Karen Bahrey

Offsetting Depression

Through encouraging a competitive nature and finding like-minded people, team sports can be an antidote to depression. More than that is the feeling of being needed, that every seat on the boat counts.

Aldine Castres, an Educational Teachers’ Assistant from Maple Ridge, British Columbia, struggles with Severe Clinical Depression that stemmed from postpartum depression and traumatic events experienced. “Neurological diagnoses are silent debilitating conditions,” she observed. “[Many] with depression suffer alone.” Being in a team where she is told she matters has been critical in her healing journey.

She recalled, “[when I started in 2012], I saw [a] boat filled with women laughing and working together. I wanted to be part of that.” Through pushing herself to try new things and not let fear hold her back, Castres is providing hope to others in a similar situation.

Dragon Boating as a Lifeline

Paddling got Carmen Bevan through the darkest moments in her life when she lost her daughter in a car accident in May 2021. The loss left her with Prolonged Grief Disorder, and she would numbly go to practice out of habit and obligation. It was her dragon boat family and paddle community in British Columbia that carried her through and kept her from self-isolating. Today, she competes in honor of her daughter.

“Paddling for the Para Team is about finding healthy ways to channel my grief,” shared Bevan. “I honestly know I would not have survived without the support of my paddle sisters and brothers.”

Photo credit: Carmen Bevan

Photo credit: Carmen Bevan

What They Wish People Knew About Paradragons

As noted by Funiciello, “We may go about things differently, but do it anyways.” In most cases, para athletes require few adaptations; they just need the chance to prove themselves.

Blind paddlers actually have an edge as they are not distracted by external (visual) stimuli. In fact, paddling with eyes closed is a very useful training technique, encouraging cohesion and attunement within the boat.

Alternatively, for para athletes struggling with invisible disabilities, there is often the unappreciated pressure to ‘prove’ one’s diagnosis in order to be ‘believed.’ “I do not want pity,” Castres firmly noted. “I want compassion through understanding and knowledge.”'

As a coach for two women’s teams out of BC’s Fort Langley Canoe Club, she commented, “When a group of people, no matter…what walk of life, can come and move a dragon boat together, that is true inclusiveness.”

Canada’s inaugural National Para Dragon Boat team is off to smash assumptions and show the world what paradragon boaters can do. Through resilience, adaptability and indomitable spirit, they will make both dragon boat and disability history. “It starts here,” affirmed Coach Milne.

Aldine Castres pacer in blue, Bronwyn Funiciello second row in white

Photo credit: Aldine Castres